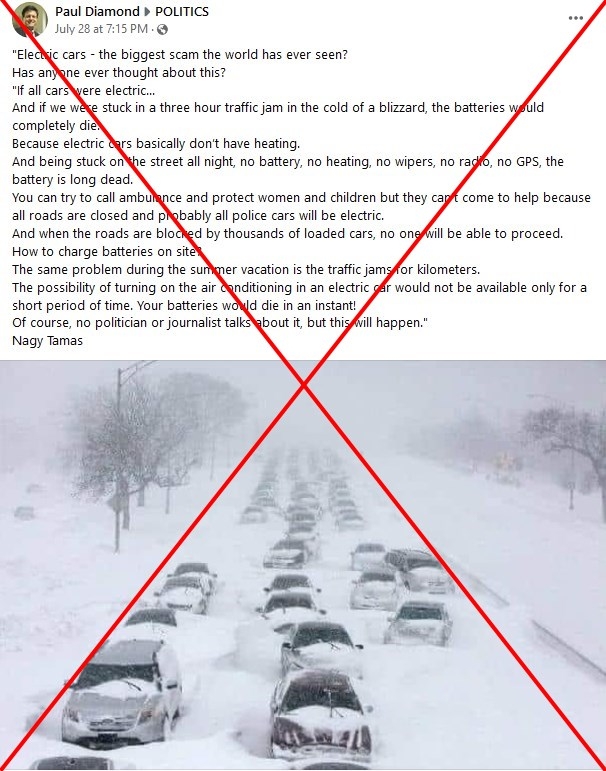

“Electric cars – the biggest scam the world has ever seen?” says a July 28, 2022 Facebook post. “Did anyone think of this? If all cars were electric… And if we were stuck in a three hour traffic jam in the cold of a snowstorm, the batteries would completely die.”

A reverse image search shows the Associated Press took the photo featured in the posts (archived here) on February 2, 2011 during a snowstorm in Chicago. It is unclear if any of the vehicles relied on electric power.

When it comes to the text of the posts, the same words have been shared hundreds of times on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. The claim comes more than a year after Canada announced it would require 100 percent of new cars and passenger trucks to be zero-emission by 2035.

Cold and hot temperatures do affect an electric car’s performance, but experts told AFP it is misleading to claim extreme weather would instantly deplete a battery.

Heating takes hours to deplete EV batteries

A 2019 Renault guide for optimizing EVs in the winter says “extreme conditions can lead to reduced range or increased charging time.” That is due in part to the use of cars’ heating systems.

“In the same way that you will quickly run out of fuel using the air conditioning or heating in a combustion engine car, these accessories also use battery power when in continuous use,” Alexis Grimaud, an associate researcher at the Solid-State Chemistry and Energy Lab in Paris, told AFP in a July 4, 2022 email.

Julia Poliscanova, senior director at the Brussels-based European Federation for Transport and Environment, concurred.

“Largely this depends on the quality of the heat technology that the battery uses, i.e. presence of a heat pump & the overall heating strategy,” she told AFP in a July 19, 2022 email.

Poliscanova pointed to studies from the General German Automobile Club (ADAC) that she said “proved that an electric car uses relatively little energy when stationary, even in winter.”

The organization tested the performance of a Renault Zoe ZE50 and a Volkswagen e-Up in a traffic jam in temperatures ranging from -7 degrees Celsius (19.4 degrees Fahrenheit) to -14C (6.6F). The cars’ heat was set at 22C (71.6F).

After 12 hours, the Zoe had used about 70 percent of its battery, while the e-Up had used 80 percent.

“This means that a 3-hour traffic jam would lead to only 18-20% depletion of the battery,” Poliscanova said.

She also pointed to reports on a January 2022 test by YouTube channel Dirty Tesla, which measured the battery performance of a Tesla X and a Tesla Y in freezing temperatures. The test followed reports of people stranded on a highway in the US state of Virginia.

After 12 hours in sub-zero temperatures with seat heating on, the model Y battery decreased from 91 to 58 percent. The model X, meanwhile, decreased from 90 to 47 percent.

“So, based on the evidence known, depending on the model and the heating technology, 8-20 percent of the battery could be used in a 3-hour traffic jam,” Poliscanova concluded.

The impact of cold temperatures on batteries has also been studied in Norway, where government subsidies encouraged drivers to buy electric vehicles.

In January 2021, an industry group announced that Norway had become the first country where electric cars accounted for more than half of new registrations.

Lars Lund Godbolt, an adviser at the Norwegian EV Association (Elbil), told AFP the country has not faced issues with EVs in winter, when temperatures drop to -6.8C (19.76F) on average.

“The (battery management systems) protect the battery and a battery works fine when it’s cold — it’s just that less of the energy is available until the battery is warm enough,” he said in a July 22, 2022 email.

“Below -20C (-4F) we see a reduction in range from around 35-45 percent,” Godbolt said. “Some of this is because of snow on the roads and that there is more resistance in cold air.”

With temperatures closer to 0C (32F), “we see a reduction of 20-30 percent depending on the EV, amount of snow, etc.,” Godbolt said. However, he noted that EVs heat up much faster than cars with internal combustion engines, which need to reach a certain temperature before they start heating the cabin.

For EVs, “an average heating system uses 6-7 kW if you put it on absolute maximum (30C or 86F). For 20C (68F) about 2-3 kW,” Godbolt said. “And with heat pumps, the already heated cabin then reuses the heat and maintains it at 1 kW.”

“With modern EVs (most of them have between 50-80 kWh batteries), you can be stuck in a blizzard and stay there for many, many hours,” he concluded.

The Quebec branch of the Canadian Automobile Association (CAA) advises drivers to plug in their car prior to use in order to preheat the battery, which will improve performance.

EVs can also run for hours in hot weather

The claim that “batteries would die in a second” during summer traffic jams because of air conditioning is also misleading.

British magazine Which? conducted a test in which a Volkswagen ID.4 electric SUV sat in traffic for an extended period of time with the AC on.

“In just over an hour and 15 minutes: We lost just 2 percent of battery from a 77kWh battery,” says the magazine’s report, published in August 2021.

Poliscanova of the European Federation for Transport and Environment told AFP that, while heating in gas-powered cars is taken from wasted heat in the engine, “the energy required for the AC is an additional consumption.”

“An air-conditioning system can increase fuel consumption by up to 20 percent because of the extra load on the engine,” she said. “In a nutshell, whether a battery electric vehicle (BEV) is less efficient than (an) internal combustion engine when stuck in traffic depends on the efficiency/quality of the battery heating system used in that model.”

AFP has examined other false and misleading claims about electric cars here.

December 6, 2023 This article was corrected in the third paragraph to say the Associated Press took the photo during a Chicago snowstorm in 2011, not 2021.

AFP Belgrade

AFP Canada

Copyright AFP 2017-2022. All rights reserved. Users can access and consult this website and use the share features available for personal, private, and non-commercial purposes. Any other use, in particular any reproduction, communication to the public or distribution of the content of this website, in whole or in part, for any other purpose and/or by any other means, without a specific licence agreement signed with AFP, is strictly prohibited. The subject matter depicted or included via links within the Fact Checking content is provided to the extent necessary for correct understanding of the verification of the information concerned. AFP has not obtained any rights from the authors or copyright owners of this third party content and shall incur no liability in this regard. AFP and its logo are registered trademarks.