In a bid to tackle the climate crisis, the European Commission plans to adopt an agreement that sets the path towards zero CO2 emissions for new passenger cars and light commercial vehicles within the European Union in 2035. This will end sales of new hybrid, petrol and diesel-driven cars in favour of 100 percent electric ones.

It is in this context that viral posts shared on Facebook and Twitter claim that the Italian government made a formal commitment to not comply with the regulation, which has yet to be nodded into law. “Italy has decided NOT to comply with the European lunacy of banning combustion vehicles in 2035. The floodgates are open, others will follow,” reads the false claim shared more than 10,000 times (1, 2, 3…) on Facebook and nearly 5,000 times (4, 5…) on Twitter since December 2022.

To support the claim, many of the authors of the posts mention either an article from the auto news site Turbo or one from the trade magazine L’Auto-journal.

Both posted online on December 9, 2022, they refer to remarks made by Italian Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini — who is also the transport minister — and quoted by Bloomberg. “The risk is that of a pseudo-environmental fundamentalism that doesn’t help the environment, but leaves tens of thousands of workers without a job… Outlawing petrol and diesel cars by 2035 while calling for a switch to Euro7 standards by 2025 makes no economic, environmental or social sense,” Salvini said. There was however no mention of a formal decision by Italy to refuse to comply with the EU regulation.

AFP also did not find any official statement of the kind in the Italian press.

In any case, the Italian government is, like every member of the European Union, required to comply with European law as defined by its treaties.

In the event of non-compliance with a regulation, it could face significant financial penalties imposed by the Court of Justice of the European Union. Italian judges could also directly penalise auto dealers were they to sell CO2-emitting vehicles beyond 2035, given that EU law takes precedence over the laws of member states, European legal experts told AFP.

EU regulation not yet in force

The posts shared on social media include several inaccuracies.

“Italy has decided NOT to comply with the European lunacy of banning combustion vehicles in 2035,” they claim. Yet, not only has the Italian government not made such a decision, but the regulation in question has not even yet officially entered into force.

Indeed, the process of negotiating, validating and formally adopting an EU regulation takes several months or even years.

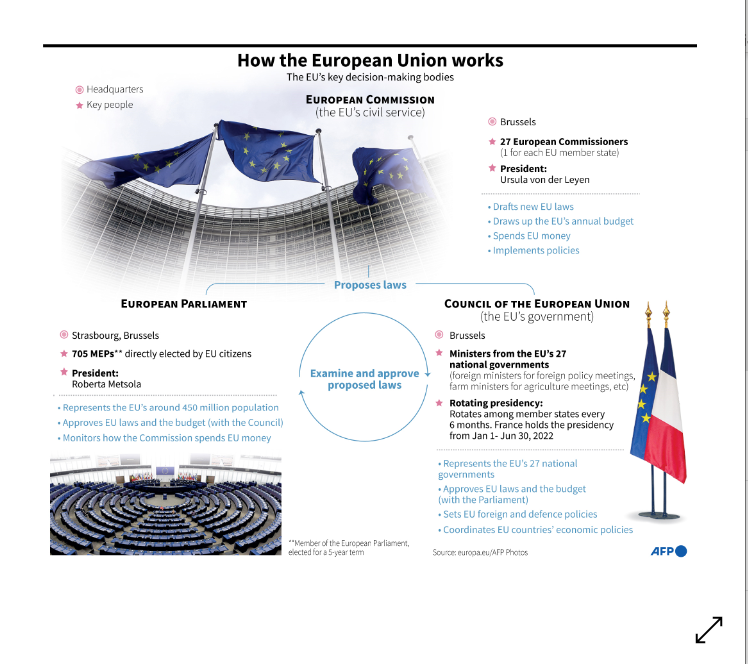

“It works more or less like your traditional legislative process,” Vincent Couronne, director of Les Surligneurs — an association of lawyers specialising in the fight against legal disinformation — and European legal expert, told AFP on January 4.

“The legislative proposal is made by the European Commission. Then the European Parliament (which is the lower house, similar to France’s National Assembly) and the Council (the upper house, like the senate), each debate the text, amend and adopt it,” Couronne said.

“In the Parliament, it’s adopted the conventional way, by a majority of votes. At the Council, it’s a bit more complex in that it’s a system of qualified majority voting,” he added.

In that system, at least 55 percent of member states must vote in favour (which corresponds to 15 of the 27 EU members) and the member states that support the proposal must represent at least 65 percent of the population of the European Union, according to Toute l’Europe, a reference site for European information.

In the case of the agreement regarding zero emissions from new cars and vans by 2035, the legislative proposal was made by the European Commission in July 2021, the member states adopted their position on June 29, 2022 during a meeting of EU environment ministers in Luxembourg, and a provisional agreement was reached by the Parliament and Council on October 27, 2022.

“EU negotiators secured an agreement with member states on the Commission’s original proposal to reach zero-emission road mobility by 2035 (an EU fleet-wide target to reduce the CO2 emissions produced by new passenger cars and light commercial vehicles by 100% compared to 2021),” the European Parliament said in a press release.

The European Parliament then voted to adopt the text on February 14. However it still needs to be formally endorsed by Council, before it can be published in the EU Official Journal and enter into force.

“The final text still needs to be approved, but it’s a formality. Political agreement has already been achieved on the matter,” Thomas Pellerin-Carlin, director of the EU Programme at the Institute for Climate Economics, told AFP on January 6.

Despite what the social media posts claim, the agreement does not ban combustion cars altogether, but instead puts an end to sales of new ones.

Leading car producer Germany has also demanded that Brussels provide assurances the law would allow the sale of new cars with combustion engines that run on synthetic fuels, and on March 25 the two sides struck a deal on the future use of efuels in cars.

The EU regulation fits into the wider picture of a package adopted by the European Commission in 2021 called “Fit for 55”, whose legislative proposals aim to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 55% by 2030 compared to 1990 levels, and achieve climate neutrality in 2050.

“It’s one of the key elements of the Green Deal, the number one priority of the European Commission, which in 2021 adopted the European climate law. This law has several objectives, with a particular focus on climate neutrality by 2050,” Pellerin-Carlin said.

Italian government is legally subject to European law

Since its inauguration, the Italian sovereigntist government has on many occasions expressed its reservations about the plan to ban new sales of fossil fuel cars from 2035.

For example, Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni said the following at her end-of-year press conference on December 29: “No, I don’t consider it reasonable. I consider it deeply damaging to our manufacturing sector. It seems to me there is cross-party agreement in Italy on the issue and I intend to make use of that consensus to forcefully raise the issue.”

The Italian government however will not be able to legally refuse to implement the accord once it comes into effect.

“Legally, a priori, Italy cannot opt out of applying the agreement. It’s a regulation: a European legislative act that member states are required to respect and apply,” Couronne said.

“What’s distinctive about an EU regulation is that it is directly applicable in all member states of the European Union. So it is first up to Italian citizens and companies to respect it. What this means is that starting January 2035, auto dealers will no longer be allowed to sell cars that emit CO2,” he added.

“Unlike a directive, which applies to member states, a regulation is a European law that directly constrains the key actors, so in this case the carmakers,” said Pellerin-Carlin.

“Were an auto dealer to decide to continue to sell this kind of engine, it would be up to Italy to punish him for breaking EU law. But were it to not do so, were Italy to fail to ensure that its dealers were no longer selling CO2-emitting cars, then it would be Italy that would be responsible vis-a-vis the European Union and which could be subject to financial penalties from the Court of Justice of the European Union for non-compliance with EU regulation,” Couronne said.

What’s more, it is not within the government’s purview to circumvent an EU regulation. Indeed, “Italy would have to amend the law to prohibit judges and Italians from respecting the regulation. Only the parliament could do it,” Couronne said. “In any case, even if the parliament were to adopt this kind of law, the Italian constitutional council would automatically condemn it for notably undermining the independence of the judiciary.”

Primacy of European law over national law

In concrete terms, the application of this EU regulation will be supervised by national judges (Italian, Spanish, French), who are directly subject to European law.

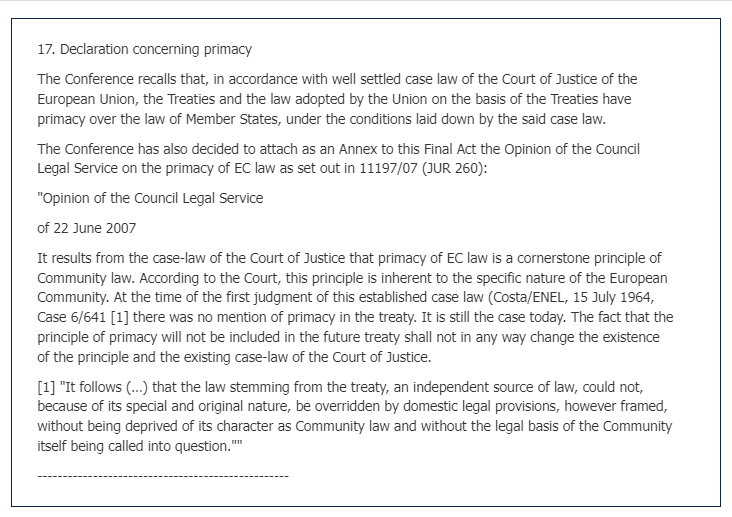

Indeed, “there’s a principle of the primacy of EU law,” said Couronne. “It is enshrined in a declaration annexed to the TFEU in which member states recognise the principle of primacy and its validity.”

This statement is available online on the EUR-Lex website, which provides official access to EU legal documents.

“If an Italian NGO of the likes of… Greenpeace so wishes, it could file a complaint in 2035 with the European court in Luxembourg — harnessing EU law — or directly with an Italian judge,” said Pellerin-Carlin.

“If there’s a conflict between Italian law and European law, it’s European law that wins. It’s what we call the principle of primacy, which says that all EU legislation prevails over national law,” he added.

No EU government will thus be legally able to waive the application of the regulation on CO2 standards for cars.

An amendment known as the “Ferrari amendment”, which was notably supported by Italian MEPs, was nevertheless added to the draft legislative text. It states that the greenhouse gas emission reduction requirements for all manufacturers in the EU market should be aligned “except for those responsible for less than 1,000 new vehicles registered in a calendar year.” This amendment will benefit Italian luxury brands in particular.

The EU has also provided for a “review clause”, to make a first assessment in 2026, but it “should really be understood as a form of political sympathy. Seeing as certain member states are against this agreement, in the spirit of compromise the European Union will take stock of the situation in 2026, but this has no legislative constraint,” said Pellerin-Carlin.

In the closing stretch of negotiations at the European Council level in June 2022, Mario Draghi’s Italy, backed by four other countries, proposed that the EU ban on new sales of combustion engine vehicles be pushed back to 2040, instead of 2035, as mentioned in the Commission’s initial proposal.

This request was not entertained because the member states had collectively decided on 2035, the definitive date.

Emilie BERAUD

AFP France

- Home

- About AFP

- How we work

- Editorial & Ethical standards

- Fact-Checking Stylebook

- Meet the team

- Training

- Subscribe

- Contact

- Corrections

Copyright © AFP 2017-2023. All rights reserved. Users can access and consult this website and use the share features available for personal, private, and non-commercial purposes. Any other use, in particular any reproduction, communication to the public or distribution of the content of this website, in whole or in part, for any other purpose and/or by any other means, without a specific licence agreement signed with AFP, is strictly prohibited. The subject matter depicted or included via links within the Fact Checking content is provided to the extent necessary for correct understanding of the verification of the information concerned. AFP has not obtained any rights from the authors or copyright owners of this third party content and shall incur no liability in this regard. AFP and its logo are registered trademarks.