Have the article read by OpenAI (Beta). Please note that AI translations may take some time to process.

Have the article read by OpenAI (Beta). Please note that AI translations may take some time to process.Migration has been a contentious issue in the EU for years. Amid a series of electoral successes for far-right parties across the bloc and a changing security landscape, individual countries take increasingly restrictive positions. Only in May, the new migration and asylum pact was adopted foreseeing tougher rules to combat irregular migration flows from summer 2026.

While calls for tougher action have been present then, they were reiterated at last week’s European Council summit where migration took centre stage – with the backing of more and more countries asking for stronger protection of EU borders, discussing externalisation of asylum procedures and a speedy implementation of rules regarding migrant returns.

Ahead of the summit, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen announced in a letter to EU leaders that in its new term the EU executive will consider establishing return hubs in third countries, where illegal migrants would be sent to await return to their countries of origin. Migration policy in the EU could only be sustainable if those who didn’t have the right to stay in the EU were effectively returned, von der Leyen wrote in the letter

At the summit last Thursday, EU leaders approved a text calling for urgent new legislation to increase and speed up migrant returns. They also called for the EU to explore “new ways” to counter irregular migration.

Though not mentioned explicitly, such measures could include so-called return centres outside the EU, modelled on a deal Rome struck with Tirana to send some migrants to Albania for processing. The idea of externalisation divides the EU’s 27 member states.

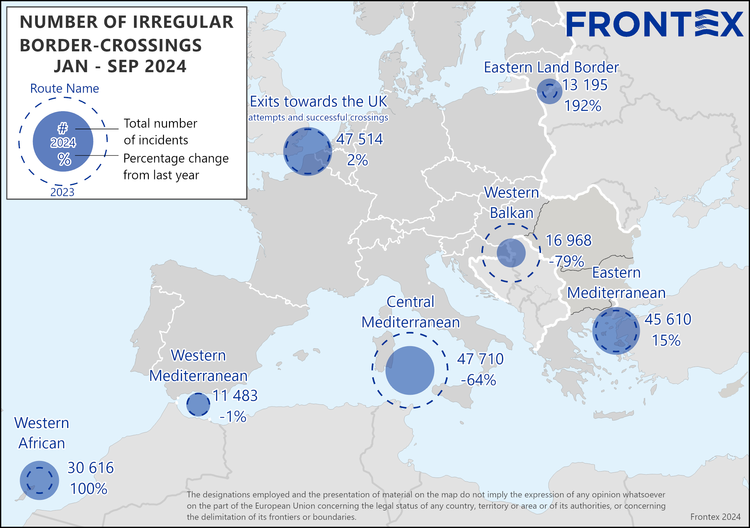

Currently less than 20 percent of people ordered to leave the bloc are returned to their country of origin, according to EU data. The EU’s border agency Frontex said illegal entries in the first nine months of this year decreased by 42 percent compared to last year – with 166,000 crossings recorded. The data shows a decline of 79 percent in the Western Balkan route, a 64 percent drop in the Central Mediterranean route while the Eastern Land Border saw a high increase of 192 percent.

Meloni’s “mini summit”

Italy’s hard-right Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni co-hosted talks on migration with Denmark and the Netherlands on October 17 which brought together centre and hard-right governments, setting the tone for the main event.

Representatives from Greece, Czechia, Estonia, Cyprus, Slovakia, Malta, Austria, Poland and Hungary were in attendance. As was – controversially – EU Commission chief von der Leyen.

Representatives of all the countries that met that morning agreed that “we must be bolder and faster in our responses”, Czech Prime Minister Petr Fiala said afterwards.

EU lawmaker and co-leader of the Greens, Bas Eickhout, said ahead of the summit that “we must not bow down to far-right fear mongering and populist propaganda on migration”.

The Italy-Albania blueprint facing hiccups

In November 2023, Italy and Albania had signed the deal for two Italian-managed holding centres on Albanian soil which started operating in mid-October. The centres are meant to house asylum seekers until their cases are handled remotely by Italian judges.

Sixteen men from Bangladesh and Egypt arrived at the Albanian port of Shëngjin on October 16.

The controversial deal has been seen as a potential blueprint of so-called “return hubs” by other EU member states, while critics call it a “new Guantanamo” that externalises the issue and is excessively expensive.

Italian judges on Friday ruled against the detention of the first migrants in the non-EU country, saying a recent ruling by the European Court of Justice (ECJ) meant the men do not meet the criteria for detention in Albania and must instead be brought to Italy.

Four of 16 were identified as “vulnerable” and were immediately sent back to Italy. The remaining twelve boarded an Italian coast guard vessel on Saturday which took them to Brindisi in southern Italy, Albanian port officials said.

The Court’s decision sparked an angry reaction from leading cabinet members, with Italian Deputy Premier and Transport Minister Matteo Salvini accusing judges of being “politicised”. Meloni responded to the ruling on X, saying “Italians have asked me to stop illegal immigration, and I will do everything possible to keep my word and stop human trafficking”.

On Monday, the Italian government approved a decree on migration defining a list of safe countries for repatriation. The measure aims at solving the legal issue regarding the migrant detention in Albania and includes a list of safe countries as part of primary legislation rather than like an inter-ministerial decree, “which a judge cannot fail to apply”, Justice Minister Carlo Nordio said late on Monday.

Italy’s migrant measures, including its centres in Albania to process migrants in Italian-run centres in the Balkan country must comply with EU law, according to a European Commission spokesperson said Monday.

“We are aware of the ruling in Italy and we are in contact with the Italian authorities: at the moment there is no European list of safe third countries, the member states have national lists, but it is expected that we will work on it,” said the spokesperson.

Looking at migration across the bloc

The tide has seemingly turned regarding the subject of migration within Europe. While many are in favour of speeding up procedures and implementing the EU’s migration pact, the idea of externalising asylum claims outside of the EU is divisive. But some countries are trying to opt out of the pact altogether.

In recent weeks, the Netherlands requested an opt-out of the EU migration pact from the European Commission – an unprecedented move, deemed unlikely to be successful. Hungary followed suit.

In October, Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk announced a temporary suspension of the right to asylum or migrants crossing from Belarus. Warsaw accuses Moscow and Minsk of pushing migrants to the Polish border, which is also an EU external border, in order to destabilise the bloc and undermine security.

Finland, which borders Russia to the east over a distance of around 1,340 kilometres, closed their shared border last year over accusations that Moscow was deliberately bringing undocumented asylum seekers to the crossings. Upon arrival at the summit, Finnish Prime Minister Petteri Orpo said he “supports and understands Poland” and called for a solution at EU level.

In Sweden, the current right-wing government aims to have the most strict view on asylum in the European Union and is proudly announcing that the amount of asylum seekers now is the lowest since 1997.

In spite of the tougher stand on migration, the government is firmly backing the new EU pact on asylum and migration, and is very sceptical towards countries that want an opt-out or want to see a Rwanda-model.

The former UK government had planned to deport asylum seekers who arrived in the United Kingdom without valid papers immediately to Rwanda. The scheme was abolished by current prime minister, Keir Starmer, on his first day in office.

The German parliament recently (October 18) approved curbs to the benefits offered to asylum seekers.The passage of the new rules marks a turning point in German attitudes towards immigration. The country has also extended border controls to the frontiers with all nine of its neighbours, temporarily suspending elements of the EU’s free movement rules.

Meanwhile, France‘s new hardline interior minister, Bruno Retailleau, has complained that EU law makes it “nearly impossible” to repatriate migrants to their home countries. The country also prolonged temporary border checks with six of its neighbouring countries including Luxembourg, Belgium, Germany, Italy, Spain and Switzerland until the end of April next year.

Summit reactions

Speaking at the summit, German chancellor Olaf Scholz called for member states to push forward with the implementation of a new EU migration agreement. He remained sceptical of the idea of external centres.

This was echoed by Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez who considers that external centres will not solve any of the existing problems but instead create new ones. Sánchez, also in favour of speeding up the implementation of the EU’s migration pact, stated that “we need to face the migration phenomenon thinking about future generations and not the next elections”.

Slovenia is among those wanting to accelerate the implementation of certain measures of the EU’s migration pact. “Slovenia advocates for an immediate implementation of measures meant to involve transit countries and countries of origin,” and for more dedicated funding in the future, Prime Minister Robert Golob said on the summit’s sidelines.

Portugal’s Prime Minister Luís Montenegro stated that the country is ready to receive immigrants but will not do so “with its doors wide open”. He further expressed the country’s support for EU mechanisms against illegal migration if human rights are respected.

Czech Prime Minister Petr Fiala told journalists at the summit that the European Union must fundamentally change its return policy, protect its external border much better and cooperate more with third countries. He further said that the solution was not to “do checks inside the Schengen area, which is what is happening now”.

Worried about ripple effects in the neighbourhood?

Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), as a key transit country on the Balkan migration route, is facing increased pressure due to attempts at illegal border crossings into Croatia. Stricter measures at the EU borders could result in a higher number of migrants stranded in BiH.

The Service for Foreigners Affairs of Bosnia and Herzegovina is not concerned about the current number of migrants, which remains like previous years. Although the situation at the borders with Serbia and Montenegro is currently stable, authorities have warned that there could be an increase in illegal entries from Albania in the coming period following the Italy-Albania agreement.

This article is published twice a week. The content is based on news by agencies participating in the enr.