The WHO called negotiations among its 194 member states in December 2021 to draft a new agreement “to strengthen pandemic prevention, preparedness and response”. Known as the Pandemic Treaty, it is being drawn up via a series of meetings.

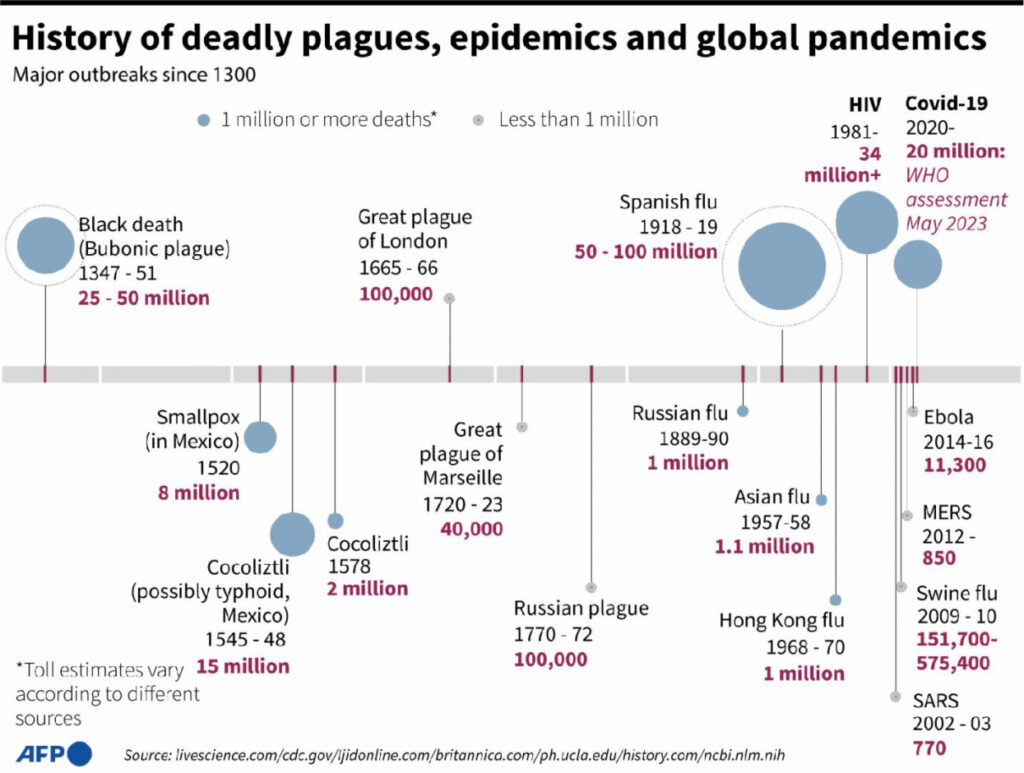

The WHO said it needed a treaty in “recognition of the catastrophic failure of the international community in showing solidarity and equity in response to the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic,” according to early drafts.

On Greek social media, widely shared misleading claims (here, here and here) show Croatian MEP Mislav Kolakusic claiming that the treaty will make countries surrender their authority to declare pandemics and procure vaccines. He said the WHO would use it to declare more pandemics in order to impose more vaccinations — around 60-90 per person. He said that this would benefit large pharmaceutical companies, claiming that they control the WHO.

These claims are baseless and misleading. The WHO does not have the power to demand that states implement policy and there is no evidence that it is controlled by pharmaceutical companies. His claim that the WHO will use the treaty to declare more pandemics in order to enforce more vaccinations is groundless.

AFP had already looked into other claims that misrepresent this treaty: here and here, in French.

The MEP made the comments at an event at the European Parliament in Brussels on July 4, 2023 that was held by the Trust & Freedom European Citizens Initiative. The event was critical of planned amendments to the International Health Regulations (IHR), which define the obligations of nearly 200 countries in handling outbreaks of disease.

Kolakusic had previously spread misinformation on the COVID-19 pandemic and vaccination. AFP fact-checked some of his claims here, in Serbian.

What is the Pandemic Treaty?

The new accord is intended to ensure that all sectors “are better prepared and protected, in order to prevent and respond to future pandemics,” according to its FAQ page.

“At the heart of the proposed accord is the need to ensure equity in both access to the tools needed to prevent pandemics (including technologies like vaccines, personal protective equipment, information and expertise) and access to health care for all people,” it says.

The Intergovernmental Negotiating Body (INB), which is leading the negotiations on the treaty, held its sixth meeting in July 2023. The latest publicly available version of the accord was published in June 2023 and can be found here.

The INB includes a wide range of stakeholders, from member countries to the United Nations and other intergornmental organisations. It also seeks input from a range of groups, from civil society to medical institutions.

The accord is expected to be submitted for adoption to the World Health Assembly in 2024. As per Article 19 of the WHO Constitution (here), “a two-thirds vote of the Health Assembly shall be required for the adoption of such conventions or agreements, which shall come into force for each Member when accepted by it in accordance with its constitutional processes.”

The treaty’s FAQ page says that it “would be expected that a new accord would be open to the participation of all countries, who would be able to participate if they so wished.”

No requirement to ‘surrender authority’

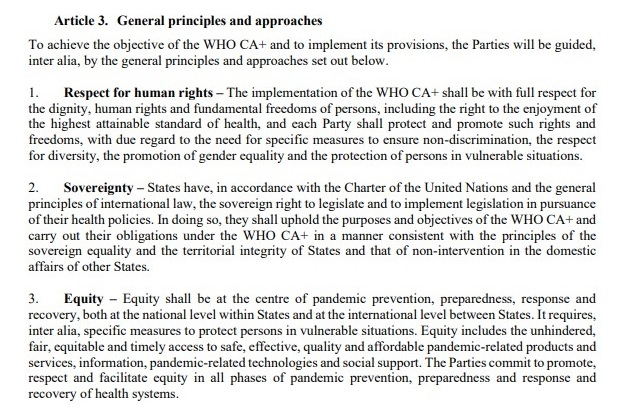

The latest version of the treaty, which is also called the WHO CA+, does not say that states must give up their sovereignty on public health to the WHO, as claimed by Kolakusic.

Article 3 upholds national sovereignty as a general principle. “States have, in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations and the general principles of international law, the sovereign right to legislate and to implement legislation in pursuance of their health policies,” it says.

“In doing so, they shall uphold the purposes and objectives of the WHO CA+ and carry out their obligations under the WHO CA+ in a manner consistent with the principles of the sovereign equality and the territorial integrity of States and that of non-intervention in the domestic affairs of other States.”

“National sovereignty rests entirely with countries responsible for making health policies for their citizens,” the WHO said in a tweet on February 25, 2023.

A WHO spokesperson told AFP on July 21 that there is “no basis whatsoever” to the claim that the WHO CA+ will transfer responsibility for public health from sovereign states to the WHO.

“The whole process is led by Member States, and only Member States can ratify the Pandemic Accord, and hold each other accountable for its implementation,” the representative said.

“Countries are still in charge of their pandemic response,” Sharifah Sekalala, professor of global health law at the University of Warwick, told AFP on June 7. “The treaty just tries to increase the level of international cooperation within this response.”

The WHO accord “does not in any way deny state sovereignty in dealing with pandemics”, Benjamin Mason Meier, a professor of global health policy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, said on June 8. “In fact, it will be drafted by states themselves,” he added.

As an international intergovernmental organisation, the WHO must respect the sovereignty of states and only has the authority given by its members of their own free will, according to Aurianne Guilbeau, political science lecturer at the University of Paris 8. She spoke to AFP in May 2023 for an article on the same topic.

“States are free not to become parties to, sign or ratify the treaty, in its entirety or only some of its provisions. If states ratify the treaty, that means they agree to its provisions and undertake to abide by it — that’s the force of law. It may also happen that some states withdraw from the treaty,” she said.

This point is addressed on the FAQ page. “As with all international instruments, any new accord, if and when agreed by Member States, would be determined by governments themselves, who would take any action while considering their own national laws and regulations,” it says.

The same document says that it is “up to Member States to decide if and what compliance mechanisms would be included in the new accord on pandemic preparedness and response”.

It points out that “it is a general principle of international law that once an international law instrument is in force, it would be binding on the parties to it, and would have to be performed by those parties in ‘good faith.'”

International Health Regulations

The new accord aims to be coherent with the IHR (here), which define members’ rights and obligations in handling diseases and emergencies that have the potential to cross borders. These are legally binding on 196 countries, including the 194 WHO member states.

The latest version was finalised in 2005, though there is an ongoing process to update them. Potential “targeted” amendments to the IHR related to the planned Pandemic Treaty are being considered, according to the WHO.

Declaration of pandemics

Claims that the WHO CA+ and the updated IHR would give the WHO the overall authority to declare pandemics and procure vaccines on behalf of member countries are misleading.

The latest version includes the option of adding a second paragraph to article 15, which is entitled “International collaboration and cooperation”. The proposed paragraph says that “the WHO Director-General shall determine whether to declare a pandemic”. However, the issue has not yet been settled.

Technically the WHO does not declare a pandemic but a “public health emergency of international concern” (PHEIC), the WHO spokesperson told AFP on July 21. This requires legally binding action by the member states, including notifying the WHO of health issues that may be of international concern and responding to requests for information.

There is “no basis whatsoever” to the MEP’s claim that the treaty would allow the WHO to declare a greater number of public health emergencies, according to the spokesperson.

There are criteria for determining whether an event constitutes an emergency. They are laid out in Article 12 of the IHR of 2005 and include information provided by member states, relevant scientific evidence and an assessment of the risk to human health and the risk of the international spread of disease.

“WHO’s independent expert committee uses three criteria to decide when to declare a PHEIC and when to lift it. A public health event must be ‘serious, sudden, unusual or unexpected; likely to spread internationally; and likely to require immediate international action,” the spokesperson said.

The same Article 12 has given the WHO the right to declare such an emergency since 2005. “The Director-General shall determine […] whether an event constitutes a public health emergency of international concern,” it says.

If a PHEIC is declared, WHO develops and recommends health measures for implementation by member states during the emergency.

The WHO declared COVID-19 a PHIEC in January 2020, with WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus characterising it as a pandemic in March 2020. The PHEIC label was dropped in May 2023.

The draft Pandemic Treaty and IHR (2005) stress the importance of information-sharing between states on pathogens with the potential to cause pandemics and epidemics. They underline the need for a “timely, safe, transparent and rapid exchange of specimens and generic sequence data”, as stated in a proposed amendment of Article 44 of the IHR.

Vaccine procurement

Unequal access to pandemic-related products such as vaccines between poorer and richer nations has been blamed for boosting the global Covid death toll. The WHO criticised pharmaceutical companies for not releasing vaccine patents and called regularly for equitable access to vaccines.

The WHO CA+ proposes tools to help with vaccine procurement and does not suggest that the WHO take over the role from member states. For example, Article 10 of the proposed agreement says that each state shall develop “policy frameworks and principles for the negotiation of procurement agreements”.

The procurement of vaccines and other pandemic-related products is addressed more directly in Article 13 of the latest draft of the WHO CA+, which focuses on supply chain and logistics. It emphasises the need “to ensure the availability, affordability of, and equitable access to, pandemic-related products.”

The draft document considers three different options for a more equitable distribution of pandemic products. All three suggest WHO involvement, for example in pooled purchasing mechanisms or facilitation of purchase agreements between buying countries and suppliers.

The proposed amendments (here) to the IHR recommend that the WHO coordinate “equitable access” to health products, including vaccines, as well as their “availability and affordability” in case of an international health emergency.

In general, national governments and health services are responsible for the purchase of vaccines. However, there have been coalitions of buyers that acquire vaccines through pooled procurement. UNICEF has, for example, led pooling mechanisms for the purchase of vaccines against specific diseases, such as polio.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, both the EU and the African Union purchased vaccines for their respective member states through pooling mechanisms. In 2020, the COVAX initiative was created by the WHO and other organisations, aiming for more equitable access to vaccines, especially in poorer countries.

No basis for increased vaccination claim

“The procurement of vaccines, and therefore the number of doses purchased and administered to EU citizens, are a national competence under the responsibility of individual Member States; ECDC does not monitor country purchases of vaccines,” a spokesperson for the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), the competent EU authority, told AFP on July 25.

The MEP’s statement that the new treaty will see more vaccines required by EU citizens is baseless, the spokesperson said, also dismissing claims that all EU citizens are currently required to have 11 each.

“There is no ‘EU average’,” the spokesperson said. From the ECDC’s website on vaccination schedules, we can see that most countries recommend more than 11. Twelve countries have made at least one vaccine mandatory for specific groups, but vaccination remains, for the greater part, optional.

In Greece, vaccines are not mandatory, but there is a recommendation of 15 vaccines for children and teenagers, as well as a few more for adults.

In France, mandatory vaccination applies to children born in 2018 onwards, and there are indeed 11 mandatory vaccine doses.

“Individuals may need more or fewer doses of a given vaccine depending on previous medical history, chronic conditions, the occurrence of natural disease, contraindications due to side effects, etc,” the ECDC spokesperson said.

Pharmaceutical companies

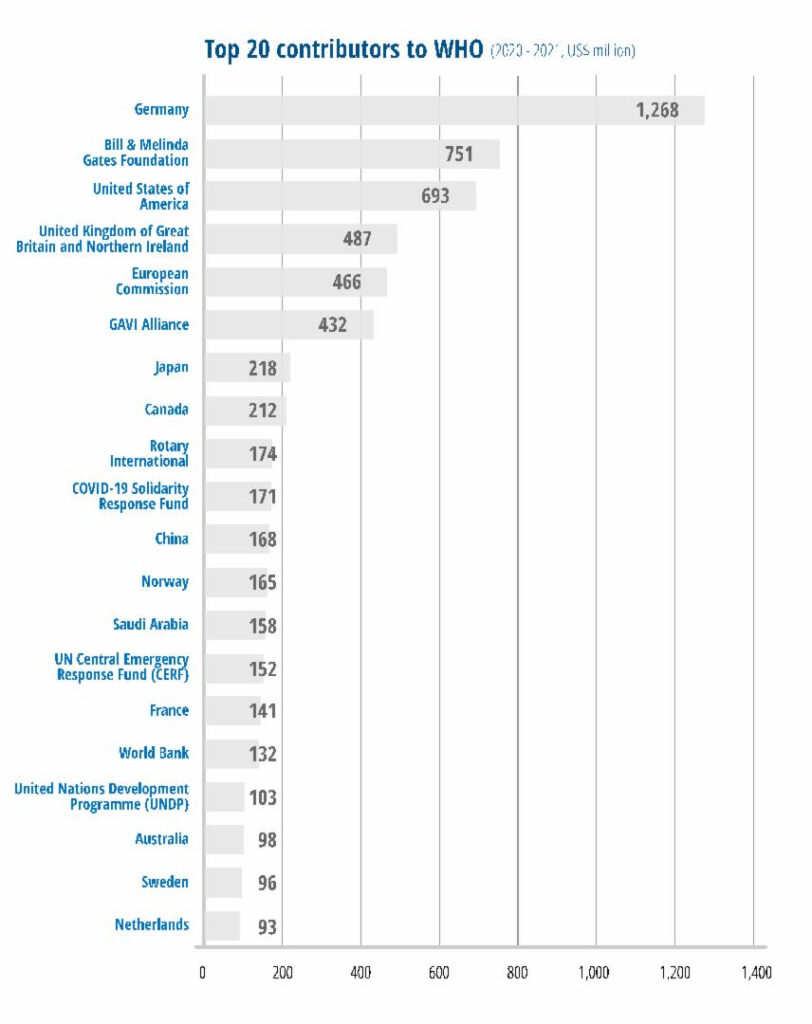

The claim that the WHO is controlled by “the owners of pharmaceutical mega-companies” is also unsupported. Even though the WHO can receive funding from pharmaceutical companies, this represents only a tiny part of the organisation’s budget.

“In 2020-21, WHO received approximately 0.75% of its budget from private sector entities (which includes pharmaceutical companies). In absolute terms, this meant US$ 54m compared to our annual budget of US$ 7 bn,” a WHO spokesperson said via e-mail on August 1, 2023.

No pharmaceutical companies are found among the WHO’s top 20 contributors, as seen in the image below. Most of them are sovereign states, while others are international governmental and non-governmental organisations.

The WHO’s budget can be found in detail on its website here.

Petros KONSTANTINIDIS

AFP Grèce

- Home

- About AFP

- How we work

- Editorial & Ethical standards

- Fact-Checking Stylebook

- Meet the team

- Training

- Subscribe

- Contact

- Corrections

Copyright © AFP 2017-2023. All rights reserved. Users can access and consult this website and use the share features available for personal, private, and non-commercial purposes. Any other use, in particular any reproduction, communication to the public or distribution of the content of this website, in whole or in part, for any other purpose and/or by any other means, without a specific licence agreement signed with AFP, is strictly prohibited. The subject matter depicted or included via links within the Fact Checking content is provided to the extent necessary for correct understanding of the verification of the information concerned. AFP has not obtained any rights from the authors or copyright owners of this third party content and shall incur no liability in this regard. AFP and its logo are registered trademarks.